Fandom is a topic I return to again and again; as somebody who grew up whetting my authorial teeth on fanfiction, analyzing my favourite FMA characters and (embarrassingly) LARPing the Pevensies in the elementary school playground, it’s impossible to avoid the ever-present role it has in my life. Even as an adult trying to build a career, it intersects with my career again and again. Anti-queer and censorship attempts affect both my fan work and my professional work; my skills as a beta reader are pressed into service again as an editor; it goes on. However, over the last ten or so years, there’s been a rising force in fandom that’s made me deeply uncomfortable, precisely because of my dual nature as a fan writer and a professional author. I’m both just somebody screwing around and having fun, and somebody trying to make this a career. I can be both; but I can’t operate somewhere in the middle and claim it’s both at the same time.

This is precisely what has been plaguing fandom for about a decade now. Fandom is stereotyped, not that unfairly, as the pursuit of the amateur. You “do” fandom because you love whatever you’re involved with so much that you want to dive into it. A fan writer creates what they do because they think it’s fun. A fan artist draws their favourite ship because it’s theirs. The word amateur itself means “a lover of something” – not that you’re bad or unskilled at something! However, increasingly, there’s a push to be professional in fan spaces, which wouldn’t be so bad if it was consistent, fairly applied, or had any actual passing similarity to real creative professionalism. Instead, it’s a Frankensteined, vague concept of professionalism that too often dips right back into amateur/fanspace politics – often when deeply inappropriate. I’m not saying, of course, that “real” creative professionals always get it right, especially in a modern social media context. It’s a frequent issue that authors or comic artists with thousands of followers unthinkingly or maliciously quote-retweet somebody small or take some criticism more to heart than they should. Even Lizzo, who I adore and would probably do literally anything for, tweeted angrily about a food courier “stealing her food” and forgot, for a moment, that she’s a global superstar who absolutely has fans awful enough to track the poor courier down. (She did pretty swiftly apologize for this one, which is why I’m pretty comfortable saying she just forgot. I would too!) But within the professional creative world(s), there are certain standards already in place, and when those standards are broken, violated or in need of updating, it’s a conversation that can take place on steady ground. The ongoing discussion about video game studios and “crunch culture” is one of these (see criticisms of Telltale Games and CD Projekt Red) , as well as other industries like publishing’s refusal to hire outside of New York City and Hollywood’s fraudulent accounting practices.

Fandom, on the other hand, has been kept in the shadows until extremely recently. It was embarrassing and possibly career-ending to admit that you wrote fanfiction, especially since it was all obviously just “gay smut” – so fandom forums were all pseudonymic, online-only, and ephemeral in the sense that if somebody left, they were just Gone Forever. If you truly became close friends with somebody, you might share personal information, but it certainly wasn’t expected. Fan artists had a touch more confidence, since even prior to this shift it was acceptable to sell fanart at conventions, but the stigma of fandom didn’t start lifting until – well, really, until AO3 was launched in 2009 and started becoming massive. Archive of Our Own’s role in professionalizing fandom can’t be understated; the Organization for Transformative Works includes a wiki for fan history, a peer-reviewed academic journal, legal advocacy for fans to defend fair use and the right for transformative work to exist, and active preservation of older fan archives in risk of shutting down, fan zines, etc. It’s the kind of project that treats fandom as a serious, worthy pursuit, and it’s not for no reason it won a Hugo Award for its organizational structure, coding and tagging.

Fanzines and Elitist Culture

Telling people in fandom that they’re not airheads for enjoying their hobby is a massive thing, and – to be clear – a good thing. But it’s not going to be without consequences. It’s a little while after the founding of AO3, for example, that fanzines start making a comeback. Historically, fanzines were small, handmade things shipped out by mail and either barely breaking even or at a loss.

“Perhaps the first media fandom type publication was The Baker Street Journal, about Sherlock Holmes, which dates back to 1946. Lennon Lyrics, the official John Lennon fan club zine from 1965 to 1968, carried factual material about John’s work with the Beatles and independently. The earliest Star Trek fanzines had a similar format… Early on, typewritten submissions were mailed back and forth between contributors… and editors, and then the final versions copied on mimeo machines (and later photocopiers) and physically collated into zines for binding.”

Fanlore.org, Fanzine: History of Print Fanzines

The revived version of fanzines were, predictably, largely electronic. However, due to the changes in the world of printing, binding, etc. they’ve become much more elegant affairs – sometimes full-size, sometimes “digest”, and often even full-color. Additionally, due to how fandom changed, they became vehicles for fanfiction and fanart almost exclusively, at least in the large cartoon/anime fandoms. What does this mean? It means that opposed to other fandom events (fic/art exchanges, “big bangs” which are essentially fic-writing and collab races, open-submission themed weeks, etc.) zines have an actual submission process. Printing costs limit the number of people who can be featured, and submission forms for zines range in complexity from simply sharing an idea you have, to giving references and sharing previous work, to actually listing previous zines you’ve in. While I’m not sure if it started in this fandom. Voltron: Legendary Defender was so over-saturated with zines that between “invited contributors” (well-known artists and writers) and repeated guests, there was a steadily-growing gap between People Good Enough For Zines, and Everybody Else. How could it be avoided, when zines need to be purchased, there’s limited money and space to go around, and you want only the best of the best?

This has a toxic effect on writers and artists; instead of creating what they want to and what they love, there’s increasing pressure to make what will “sell”. Perhaps not in the traditional sense – but first, you have to “sell” the idea to a zine mod (and as several people have brought up, hope that it also doesn’t get stolen), and then you have to write/draw it in a way that will “sell” the zine – sometimes for profit, sometimes to support a charity, but either way, to bolster your brand. And supporting your brand means more commissions, or more zine invites, or more Redbubble purchases. You want to be in zines, because you want exposure, but if you want that exposure, you have to write the right ships, and in the right ways, and impress the right people. And it has a toxic effect on fandom consumers because – quite aside from the fact that there’s a much more rigid line between consumers and creators in fandom than there used to be – there’s suddenly an Elite Class of fandom creators. Sure, you write fanfiction, but do you write good fanfiction? And if you write bad fanfiction, what’s the point? This leaks into big bangs and exchanges too; if you don’t get a “good” gift, then you feel let down, even though somebody put work into it! And if you don’t have “good” art, why claim or post for big bangs?

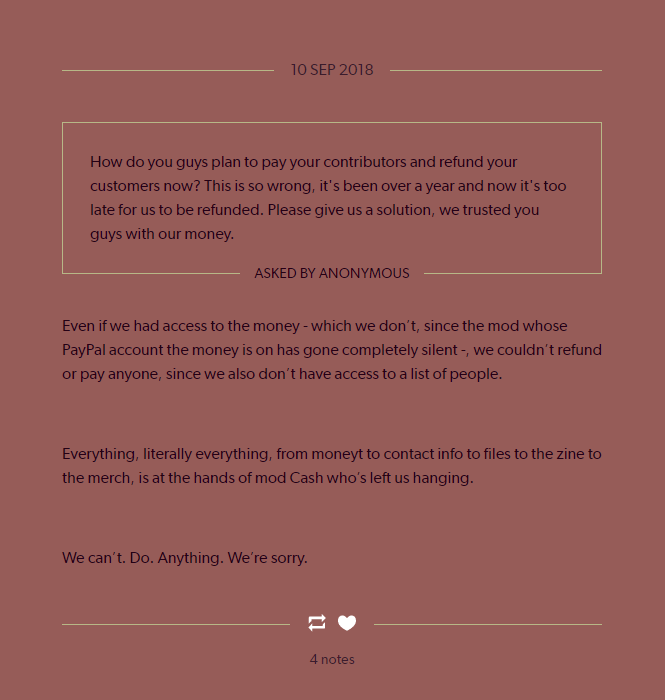

Clearly, the main issue with this is capitalism. It’s hard to avoid the need to monetize hobbies when the economy is crap and people need money to live. But if any of these were treated professionally, perhaps it would feel less overwhelming. Zines create a certain degree of elitism on their own, but the elitism wouldn’t sting so badly if there weren’t so many examples of zines simply stealing money. Consider Eternal Eclipse, a beautiful horror zine for the Voltron fandom, that after some time of radio silence, announced that one of their mods had simply disappeared.

(For those who want further context; here is the Wayback Machine link to the blog; the Tumblr blog is still up but has mysteriously deleted a number of these posts. Whether or not that means the zines were shipped out is unclear, but given that as a contributor I never received a copy or an email, I’m highly doubtful.)

This is far from a one-off. Stories about zines that never shipped, shipped after years in hiatus, emotional abuse and exploitation on mod teams, issues with credit and payment, randomly kicking contributors over ship discourse, and worse abound.

“Bungou Stray Dogs Fandom: The zine, which was for free, took over a year to published after completion. During this time, mods ghosted the entire server for months and when they did review our work, couldn’t give any good criticism. Additionally I had the massive issue of the writer mod critiquing my grammar and punctuation according to the american grammar style despite me repeatedly reminding them that I Am Not American. There was also the issue of getting these critiques a literal day before the supposed “deadline” in the middle of exams. Followed by more ghosting.”

Anonymous contributor (from the English-speaking Caribbean)

“I was one of the editors of the Shidge [Shiro x Pidge] Zine. The head editor was really difficult to work with. They demanded a lot of my time and effort and acted as though this zine should be my first priority, even though I made it clear to them that making it through my senior year of college was my top priority, and that also included relevant extracurricular activities. So when I didn’t show up to a meeting or discussion after saying upfront that I’d have to leave early or something came up, the head editor would chew me out. They would attack my ADD and say things like it’d be a miracle if someone hired me because of my lack of organizational skills. (After the problems piled up)…the rest of the editors banded together and made a post on tumblr where we warned everyone in the shidge community about the head editor’s behavior. (…) Unfortunately, the head editor basically held the zine hostage for two years, and it got to the point where I called them and told them that they needed to ship things out. (… )That seemed to be effective enough to get the zines people had been waiting 2 very, very long years for.”

d0g-bless

And even beyond that, issues with professional boundaries persist; while the concept of a Shiro Pin-Up Zine is perfectly fine, a contributor took it upon themselves to give a copy to Josh Keaton (Shiro’s voice actor) publicly at a panel.

The question is, where is the accountability? Because fandom is still so used to anonymity as a reasonable expectation, and it’s much harder to track a username than it is a legal identity, the same mods often crop up over and over again. Additionally, because many people are not participating both in fandom and professional lit journals at the same time – or certainly not with this intensity – it doesn’t occur to the vast majority of fans that this isn’t business as normal. Sure, it sucks to have your money stolen. But for the nineteen-year-old Jojo’s Bizarre Adventure megafan, it’s not immediately obvious that zine purchases aren’t supposed to be a Russian Roulette, and that people running them aren’t supposed to make you feel awful. Lit journals and magazines aren’t immune to this, but sites like Writer Beware exist precisely to warn writers of the bad ones. There’s also the unfortunate effect that the more accountable somebody makes themselves, the more the unreasonable accusations will stick to them (e.g. “they’re a predator because they ship this”, “they were mean about this fandom thing”) which, once again, makes anonymity desirable. The toxic people deliberately keep themselves untrackable; the ones with good intentions are honest and look worse by comparison.

Finally, of course, there’s the unavoidable detail that zines are not legal. You can’t enforce anything legally against bad zine mods when zines see the grey area that fanfiction and fanart (not for profit) exist in and zoom right past it. Charity zines just about manage fair use, but that’s about it. And this brings us to the role of money in fandom’s professionalism problem…

Merch, Copyright and Getting That Cash

Above, I talked about how fandom content creators are pressured into creating a “brand”, and that’s a big reason why zines create “standards” for fandom, even passively. But when it comes to zines, brands and cash, there’s another massive factor: merch.

Merch exists in the same area as zines: it really, really isn’t legal. No two ways about it. Fanfiction and fanart are legal because no money is being made off of them. Commissions, while debatable, have an argument for legality because you’re paying for the service of the creation of a then-free item – but merch is allowed to exist simply because of the tolerance of the copyright holder. (Of course, I say ‘no two ways’, but both the nature of fanfiction within copyright and the ethics of copyright law itself are hotly debated. Strikethrough was largely targeted at sexual content, but also hit at fanfiction conceptually, and the current lawsuit against the Internet Archive, while reasonable in and of itself, ignited discussion about what the parameters of copyright should and shouldn’t be.)

One thing that was an important point in the Internet Archive discussion is also relevant here; copyright may be unethical in a perfect world, but violating it impacts smaller creators the most. Most large fandoms are for corporate media, so this isn’t an issue. Voltron: Legendary Defender and She-Ra: Princess of Power aren’t in particular danger from people posting fanart to Redbubble or making keychains (especially since VLD, notoriously, had terrible official merch). But once you get into book or video game fandoms, the game changes. Holly Black, author of young adult literature such as The Cruel Prince and The Spiderwick Chronicles, became the subject of immense backlash just over a year ago when she announced that she would be teaming up with Topatoco for merchandise, and protecting her copyright. Prior to this, like most YA authors, she had been ridiculously permissive about people making money from what was essentially her property – many took it as a betrayal, while others were confused why it hadn’t happened sooner. It’s important to qualify here that authors do not make a lot of money; even successful ones like Holly Black or Seanan McGuire are comfortable at best.

The same issue arose recently with fandoms for indie video games Hades and Among Us; polite requests not to make merch for the games have been ignored or taken as insults. However, when Supergiant Games (creator of Hades) did release a merch policy that allowed merchandise to be made, it became clear that there was a distinct gap between those with professional experience, and fans who hadn’t learned those terms – mostly over the term ‘handmade’.

“Basically handmade is stuff produced by you, specifically, and mass-produced is something you’ve contracted out to a manufacturer, even if not in massive quantities. Me printing giclee prints with my own printer is handmade, me outsourcing giclee prints to Inprnt is mass-produced. The reason this is significant from the company’s perspective is scale potential. There’s only so much you can manage on your own, even if you have professional tools, whereas manufacturers have significantly larger production capabilities.”

Aleta Pérez

It wasn’t clear to many fans that home printers would still count as handmade, for example – and because of fan norms about professional vs. amateur work and considering “professional” creators as the enemy, corrections weren’t taken as well as they should be.

Ultimately, fan merch is always going to exist; but merch creators exist in the same pseudo-pro bubble as zine makers. They’re well aware of the stigma that it’s “just” fan stuff, and operate under that mentality, but are still selling a product and operating within a professional industry. And because purchasers of said fan merch are frequently (depending on the merch and fandom) equally unaware of the norms of the industry, a lot slides by that shouldn’t. Somebody selling, say, apple butter at a farmer’s market has to learn how that market works, and the norms of behaviour and product expected from that industry – but fan merch often sidesteps the normal ways of entry, with bizarre consequences.

So already with these two examples, it’s clear that as money, brand, and “real life” intrude more and more on fandom, the threads of professionalism and amateurism tangle in ways that cause inevitable hurt. You can be everybody’s friend and run a cool awesome fan event where everything is fun and low-stakes, or you can create something to high standards that you’re selling for money; but trying to do both is going to get people hurt. If nothing else, DashCon should have taught that lesson.

Fanexus, Cults of Personality and Fandom vs. Business

All of these are frustrating, of course, but so far, none of these have intruded into the unexpected for fandom. Spending money on badly-considered fan-ventures is practically a rite of passage, even if it’s more common than it used to be. But now we come to the issue that actually motivated this article. What do you do when somebody attempts a start-up company and runs it with the same dynamics, motivations and in-fighting politics as fandom, and nobody sees an issue with it?

Fanexus, as described on its own site and by Fanlore, is an “upcoming fandom-focused platform”. It’s modeled after other social media sites, probably the most notably Tumblr, but with cues from Pillowfort, Dreamwidth and other fandom-focused platforms. Most importantly, Fanexus seeks to be a social media site that is completely anti-bullying; that is, anti-shippers and other censor-happy members of fandom would straight up not be welcomed. Twitter, infamously, does not take reports of brigading seriously, and is just as likely to temporarily suspend somebody accused of pedophilia for completely chaste drawings of a frog and a princess as they are to even reprimand a TERF for consistent misgendering and death threats. Obviously, the “pro-shipper” contingent of fandom has celebrated and eagerly awaited this ever since it was announced, the flames only fanned by Tumblr’s infamous porn ban. (Pro-shipper, pro-fiction and anti-censorship are labels that, in fandom, largely refer to the same or similar things; a refusal of the “anti-shipper” perspective that says ships and characters should reach some moral standard, and that fiction should be held to the same ethical bar as real life.) In the months since, Fanexus’s mystique has only increased, with proshippers even half-joking that they’re counting down the days until the beta launch, joining the discord server, and drawing lewd art of a personification of the site as a tongue-in-cheek promo.

However, from early on, Fanexus has been plagued with controversy. Their close allyship with the deeply controversial Prostasia Foundation has inspired criticism, as well as its stance on “MAPs” (Minor Attracted People). The actual nature of the debate pales in comparison to Fanexus’s actual handling of the question; people who questioned the decisions of the mods were put publicly on blast for months on end, and are still facing blowback.

“I raised concerns in early august about Tox’s past and what that meant for Fanexus, which resulted in severe harassment from Tox and his supporters, and… I was given incorrect labels (such as “anti”) in an attempt to discredit me. When that didn’t work, I received death threats, and Tox even aided one avid supporter who had attempted to doxx me.”

-BoomerSlayr9000

Nor was this an isolated incident that could be blamed on the difficulty of any discussion about pedophilia and mental illness. The thread from @euladarnus below chronicles another example of unprofessional behaviour from Fanexus mods in early October.

[“Fanexus’ dedication to fostering a safe community on their platform has been so successful as to make me feel UNsafe on THIS one. The fact people REPORTED MY POSTS & a head mod feels comfortable insinuating “we have people everywhere” like some sort of veiled threat? love it”

“the chain of events, to be clear: i said i was uncomfortable with a social media platform requiring an application where your other [social media] is checked for approved content & had ethical concerns. somebody reported me to the mod. mod replies to ~~explain the vetting process…

…and I block because it’s not worth trying to explain at 5am that my issue is with the fact that a vetting process exists at all as opposed to banning harassers after they’ve actually done something. the mod complains about me blocking, and then continues publicly ranting about…

…how fanexus wants critique, just not…critique their mods dislike, apparently. ok. cool.

let me clear. i said on my personal twitter, with no names used, that i was uncomfortable and would not use the platform unless changes were made because of my personal ethical concerns. i also made clear that i have no issue with people who don’t find this personally concerning…

…or who do but prefer to use the platform anyway because of whatever reasons, and that i simply did not feel comfortable with this approach and so would not personally use it. and instead of whoever personally follows me who is a mod DMing me to address those concerns privately, it was…

…sent to a head mod, to be responded to publicly… “put on blast”, i believe the kids say these days lol (and completely missing the point of my criticism in the process) then complaining when i blocked to disengage.

not handled well, guys.

anyway, feel free to unfollow, soft- or hard-block me at your leisure. i’m really fucking uncomfortable with this and i wish that it had been dealt with with even a shred more maturity than the mods have shown.

it’s 6am and i’m gonna go make myself some tea now.”]

The thread is included with permission and linked to the thread on @euladarnus’s twitter. Several weeks after this encounter, she received a message claiming that the mod who had harassed her had been dismissed from the team – however, the mod dismissed was not the one who had harassed @euladarnus, but instead, the mod who later came out with stories about being abused and scapegoated by the rest of Fanexus’s mod team. And even quite aside from that situation, the public tweets from the mod actually responsible at the time are deeply unprofessional and concerning on a number of levels.

[“For the record, I’m not trawling the fanexus tag for posts. i’m being linked these posts by mods who are following the posters. turns out we have staff from all reaches of fandom!

‘but why are you they linking these posts’ because i’m Fanexus Tough Love Daddy and i usually take this sort of task upon myself”]

“i’m appalled by the lack of professionalism from the mod team… at the end of the day, i simply don’t trust a group of people who seem to engage in online harassment as a hobby to moderate a site with the vision of ending online harassment.”

euladarnus

Another concerned onlooker had this to add.

“I have a friend who was one of the mods and one of the other mods started harassing them. The other mods just let it slide, started going after my friend as well or ignoring what was going on, and forced my friend to give up their position due to bullying. If the mods are willing to do that amongst themselves and let that slide, then their site isn’t going to be the safe haven they claim it will be. I’ve been on Twitter long enough to know that if thats how they’re acting I’d be safer on here.”

Anonymous Contributor

And yet another was willing and ready to share information from the discord, but was too scared to reveal their identity to me directly – terrified of reprisal from the Fanexus mods themselves. This hasn’t stopped multiple other people from sharing screenshots and experiences in the Fanexus tag – from calls for accountability in the discord itself to mods not being clearly identified as mods.

Yet this hasn’t stopped many from brushing this off as “drama”, pettiness or unnecessary fighting. Fandom, after all, has no shortage of callouts, complete with screenshots, tagging, and taking sides. Why is this different? Well, here’s a clip from Fanexus’s FAQ:

“Right now the beta is being paid for by the founders. Once the beta is online and in use, we plan to have a Kickstarter to fund the development of additional features we couldn’t afford to include in the beta. Fanexus will be freemium, which means it will be free to use, with premium features such as added customisation, that will be used for the ongoing funding of the site.”

(fanexus-dot-net.tumblr.com)

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with this model – nor is there anything wrong with a beta being paid for by its founders. Most start-ups run this way. It’s expensive to start a business, and it’s like gambling. You sink a bunch of money into it and you hope it works out in your favour. But the key word here is business. Unpaid or paid, free to use or premium, Fanexus is stating an intent to work as a business. They’re putting money into their beta with a hope that they’ll be getting it back. No websites are free; Archive of Our Own, Wikipedia and Gutenberg are constantly running fundraisers, and Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook advertise to their users in order to cover their costs. Discovering the source of funding for any social media or website is a crucial part of understanding its intentions; if a site doesn’t have advertising, it’s getting its money from somewhere, and you have to be able to trust that funding. And already, this sets Fanexus well apart from a forum on Gaia Online or a group on Livejournal; these aren’t mods of a casual fandom event. These are founders and shareholders of a business. Ultimately, too, language matters; the insistence of the founders in calling themselves “mods” and putting all “mods” on the same level (it’s actually unclear exactly how many mods there are) disguises how many of the mods have provided funding from their own pockets to get the site going, and how many are expecting eventual reimbursement of that funding in time. In addition, while it’s possible that all of the founders are providing equal amounts, even equal amounts of money will affect different people in different ways; so who is providing the bulk of the funding? Is one of the mods working from a trust fund while another is struggling with two jobs? Again, it’s unclear, and shouldn’t be.

Immediately, once Fanexus is reframed from a fandom forum to a business with shareholders and funding, a lot of the behaviour they display becomes more suspect. It’s hard not to remember, for example, the chilling anecdote about Cards Against Humanity putting their single Black employee in the psych ward for speaking up against racism. It also becomes less useful to ask why fandom can’t rise to the standards of professionalism of the non-fandom world, and more useful to ask why unprofessionalism and workplace abuse, when it happens, isn’t treated the same way. After all, when you really think about those big bangs and volunteer-run boards, exchanges, fandom discords… that’s an awful lot of volunteer work done by people who end up being treated like crap. It shouldn’t take an actual company with money involved to start questioning whether or not this is an okay way to treat people. Even without that, the burnout of unpaid labour is already well-contested in fields like publishing and activism.

It doesn’t stop there, though. The recent callout from an ex-mod shared screenshots from inter-moderator and in-team discussions, without names censored. Immediately, those trying to protect Fanexus – both mods and eager fans – began to bring up privacy concerns. “Couldn’t this have been done in private?” they said, resoundingly, and even without the repeated answer that private intervention had been tried… Is Fanexus a company or not? Is Fanexus accountable or not to a public group of people? Should Fanexus’s mod team be public information or not? It’s a worrying statement to hear that the Discord username of a moderator of a social media website should, somehow, be considered private information – when all hopeful users of this site are currently on the same Discord. It also doesn’t pair well with a tweet linked earlier, that I’ll touch on here again.

[Rooftops: Hello? did i do something wrong?

paris [Mod]: Hello. We wanted to talk to you about a rule violation. A mod attempted to react to the message you were engaging with but clicked yours by mistake and discovered you had blocked them. Please keep in mind that it is against the rules to block mods. Please unblock all moderators you have blocked and note that you may request any mod to not interact with you instead. Any further violations may result in being removed from the beta. Do you have any questions?

Rooftops: okay

which mod was trying to ask me a question?

paris [Mod]: It wasn’t that a mod was trying to ask a question but trying to add a react to a message and clicked on your message instead.]

In this Discord screenshot, it’s made clear that people are not supposed to have any mods blocked… and in the linked thread, it’s indicated that Fanexus’s Discord has an excessive amount of moderators, not clearly listed. So essentially, on the Fanexus Discord, you aren’t supposed to block anybody, because they might be a moderator. And you can’t screenshot and share anything without redacting names, because you might be exposing a moderator. And you can’t expose a moderator, because everybody has a right to privacy, even if they’re a moderator for a public business. In short, Fanexus’s practices, no matter how terribly they behave, must stay private at all costs, otherwise the whistleblower is the actual bad person – and their behaviour towards all whistleblowers or even concerned bystanders so far certainly proves this true so far.

So what should be happening? The conversations about capitalism, “emotional labour” (and its divisive, multiple meanings), payment and expectations are ongoing, and a whole entire book in themselves. But when it comes to professionalism in fandom, quite simply, people need to pick one. Either fandom can be just for fun; you write fic and draw art with your friends, you perhaps bat some money back and forth for commissions, you do some silly things to screw around with ideas, but ultimately real life comes first. Or, fandom is a world of events, full websites, hosting, moderation, where people are penalized for missing deadlines, there are mediators for conflict, and products are held to a certain standard. These worlds aren’t even entirely mutually exclusive. The first can exist inside the second; but for the second to exist, it needs to be acknowledged that moderation is a job. Event planning is a job. Graphic design, server hosting, website design – those are all jobs. And even if unpaid, there is a contract involved; treat the people performing those duties with respect and professionalism, and those people will treat you with the same. A moderator for a zine or a website shouldn’t be making decisions based on personal grudges, and if they want to, they should be moderating something not masquerading as a professional product.

The Future of Fandom in a Post-Capitalist World

I’ve mentioned it more than once, but the true tragedy of all this is that it’s a reaction to an outside influence. Young and growing adults terrified for their future monetize the only thing they feel good at; and the gatekeepers of the “professional” versions of these industries won’t give chances to people who haven’t already proved that they’re good at it the Real Way. Most writers can’t afford to finish a book and shop it out three hundred times to “proper” publishers and agents when they have rent to pay – and the still-sneering attitude of many older writers towards fandom keeps people stuck in those bubbles. And when fandom doesn’t yield the money required, people just try harder, because they must just be missing something – forgetting that fandom was never supposed to be about money in the first place.

So what would fandom look like, breaking out of the pseudo-professionalist bubble? Many of our current standards of professionalism, admittedly, need updating (although creative fields have always been better about things like, say, piercings and tattoos). Fandom has just as much to give to the non-fandom world as vice versa; it just has to be willing to have the conversation, and it is starting. A willingness to accept that a fan-run site like AO3 or Fanexus should and is held to the same standards as Wikipedia or Twitter is a good start; while size and good intentions will get you off the hook for a while, it only gets you so far.

However, I think a big part of is also letting go of fear. There’s a sense of a ticking clock hanging over fandom, all the time. Fandom is dying; fandom is in danger; if you don’t write better fanfiction or save this show, or support this ship enough, or promote this or that website, then fandom will die. This is nonsense. Fandom’s existed since Sherlock Holmes, and even before that. Fanexus wasn’t going to save fandom because fandom doesn’t need saving; zines were already a revived version of something fandom already did, and merch copyright isn’t going to kill that desire to create just because you can’t make money off of it. There’s a running thread of fear that if we hold people who act unprofessionally, rudely or straight up abusively in our spaces to account, we’ll lose something important and irreplaceable. It isn’t true. Fandom starts and ends with you, something you love and the question ‘what if’. The rest is commentary; go and learn it.

2 responses to “Behind The Curtain: Modern Fandom and the Scourge of Pseudo-Professionalism”

Hello, I haven’t finished yet but there’s a missing word on the transcription for the discord conversation between Rooftops and paris[mod]. On the second message “[…] you may request any mod to interact with you instead.[…]” it should be “you may request any mod to /not/ interact with you instead.” Since it changes the meaning of the sentence I thought I should let you know before I forget.

LikeLike

Oh dear – thank you for catching that one, Arva! Transcribing is always a bit of a nightmare, I’ll go fix that right away.

LikeLike