Hello everyone! The GULA crowdfund is in its last week and we still have quite a ways to go — so if you want in, now’s the time! Check it out on BackerKit over here.

While I’m here, I want to talk a bit more not just about GULA itself but its inspirations. I grew up surrounded by poetry; a deaf child of hearing parents, I learned to talk and read at the same time through phonics, and poetry with its rhythms and meter was and is as natural to me as breathing. My mother ran with my passion for reading as far as reading Midsummer’s Night Dream with me when I was four, and I went to the premiere of Fellowship of the Ring with my father at the age of six as probably the youngest person there, let alone the youngest person to have already read the books. As an adult I wonder how I did it — but Tolkien’s prose is so deeply in love with itself, with the flavour of language and the inherent beauty of whatever it’s describing, that it makes sense to me that the young poet was just along for the ride. I had young readers’ versions of Edgar Allan Poe, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Christina Rossetti — and I was writing (mixed-quality) pastiches of the Brownings and Coleridge before I was in second grade. (Side-note: There’s nothing funnier than asking a teacher in the middle of class what ‘eunuch’ means.)

At the same time, the western poetic canon — as talented as many of its occupants are — is a limited one. I grew up in Britain then Canada, and I grew up blissfully unaware of my mixed-race heritage. Maybe not that blissfully. I was conscious of looking different — but my only framework for ‘dark’ was Heathcliff or the ‘raven-haired’ heroines of Tennyson or Wordsworth. It’s a tremendous failure of both school systems and the adults around me that the first poet I encountered of any measurable racialization was William Carlos Williams — a white Latino child of white Latino parents! I sought out more as an adult once the absence became obvious, and that’s how I’ve filled my bookshelves with Simon Ortiz and Langston Hughes, but also the fantastic spread of poets and poetic writers in the modern day — some traditionally published, some taking to the digital crossroads of the internet to make themselves heard.

The Arrival of Rain by Adedayo Agarau is one of these — fantastic, heart-rending verse with imagery I wish I could even come close to. (Published by Vegetarian Alcoholic Press – find it here!)

broken every time the door opens/or is banged against your face/you can count your losses/but do you remember my name?

There’s also acclaimed poet Ocean Vuong, and Night Sky With Exit Wounds — which I can hardly praise more than its other adorers. After years of queer confessional poetry about relationships and love alone (which has its place!), the emotions in Vuong’s work — both the first time I read it and every subsequent time — hit so much closer to home.

Don’t be afraid, the gunfire

is only the sound of people

trying to live a little longer

& failing.

There’s also Azad Ashim Sharma’s collection Boiled Owls. It sounds strange to say that I’ve read so much more work about addiction and mental illness from white people, but it’s true. Despite BIPOC being so much more at risk, we’re given much less space to express ourselves on it, and certainly to have complex feelings about it; Sharma’s poetry is frenetic, jagged, sometimes mean and then apologetic in the same phrase, and honest in a way that we’re so rarely allowed to be. (Boiled Owls is probably the most recent work on here, published by Nightboat Books in 2024 — check it out here.)

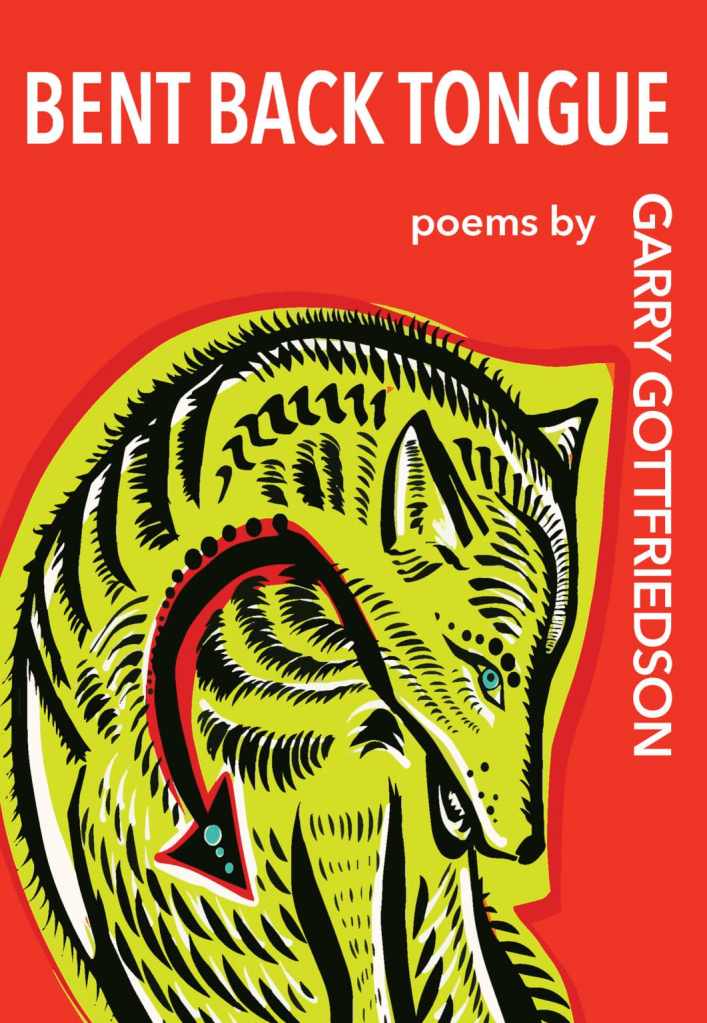

My final modern shoutout is Bent Back Tongue by Garry Gottfriedson. One of the strange hangups one acquires when growing up largely on old poetry is a sense that it’s vulgar or inappropriate to write directly about modern events — amateurish, perhaps. I’ve been consciously aware of how bizarre (and classist, and racist, etc.) that notion is for years, but I think Gottfriedson’s work finally kicked me of it at last. Gottfriedson is a Secwépemc poet in Kamloops, B.C., and Bent Back Tongue is at times bilingual, but always direct and beautiful in its directness.

Canada, you have claimed this July day

to boast the day of colonial takeover

a perpetual death warrant for my people

and a day in which you have held

your own citizens in scorn

when in fact, they are blameless

to your contempt and cover-ups

and bear your sins.…

The kind-heartedness of Sikh and other

strangers shedding tears with us

reminding us of this simple word

tsqelmucwílc — “I have returned to being human”

and for this I celebrate.

There’s power in pointing at the problem, at the issues, and saying, you, you are the cause, you are the knife, you are at fault — even when the metaphor is more comfortable. More comfortable for who? Certainly GULA uses its share of metaphor — but I don’t want to pull my punches, either.

But the past has its things to tell me, too. Langston Hughes and James Baldwin are giants in the African-American/Black American tradition, as are Maya Angelou and Audre Lorde; it will shock you then, possibly even the white Americans among you, to learn that I was an adult before reading any of their work. (Canada has a reputation as being more open-minded, more progressive, and legally in some cases that’s true; but culturally and educationally, we’re often behind parts of the States. Weird to imagine, I know.) Can you imagine how it felt, as a shattered wreck in a hospital room trying to piece my life back together, reading Still I Rise for the first time? Audre Lorde’s A Litany for Survival is one of those poems that still ghosts around the edges of my subconscious, so strongly that it’s strange to remember that I was twenty-two when I read it.

It’s also important, in my criticism of the Canadian literature curriculum, to introduce this particular poet in context. Grade 12 is when teachers, after all, have plenty of sway over their own classes; certainly if he’s the only one, it’s still a problem, and my experiences are also nearly two decades old at this point. But Omeros by Derek Walcott, published 1990 (so right between modern and older, I’d say) is a book-length epic retelling the Iliad on the Caribbean island of St. Lucia. It’s gorgeous, immersive, and I did not appreciate it nearly enough when I first read it. It’s only in the years since that it keeps coming back to me, in bits and pieces; the mastery of language, the allusions, and — most of all — a section when Achille goes on a journey not to the land of the dead (as Odysseus does in the Odyssey, although he rather summons them) but into the darkness of Africa and through the lives of his unknown ancestors. Sometimes the strongest influences are ones you aren’t even conscious of at the time — books you never would have thought to pick up on your own.

Anyway, there’s my rambling on my poetic influences! It would mean a lot to me if you’d pledge to GULA and help me make this book a reality. You can check it out on BackerKit over here; you’ve only got until December 3rd!